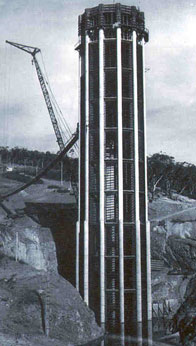

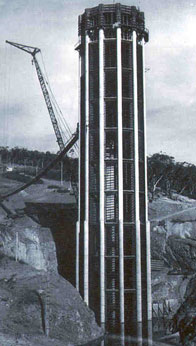

The inlet tower during construction. The trash racks down it's length can be clearly seen.

The Men From Snowy River

By David Strike

Australia's most ambitious civil engineering project teetered on the brink when, in 1961, sluice gates governing the flow of water from Lake Eucumbene - a key element in the Snowy Mountains hydro-electric scheme to divert the course of the Snowy River - began to leak.

The inlet tower during construction. The trash racks down it's length can be clearly seen.

The major catchment area for the Snowy River and its tributaries, excess water from Lake Eucumbene would ultimately be directed through the Great Dividing Range and provide year round irrigation to the low lying inland districts of southern New South Wales and Victoria. Control of the water flow was essential to the project's success.

Presented with the problem of stopping the leak and removing its cause, an accumulation of construction material that littered the inlet tower's base at a depth of 260-feet, the only practical solution was to send down divers.

No easy task at a height of 4,000 feet above sea-level, with winter approaching and water temperatures beginning to fall below freezing point.

It was a job whose problems were magnified still further by the need to carry out meaningful work in water depths far beyond the scope of normal air diving operations.

At the request of the Snowy Mountains Authority, a team of Royal Australian Navy Clearance Divers, (under the command of Commander M. Batterham, OBE, Assistant Director of Underwater Activities for Australia), were despatched to tackle the problem.

Working from a pontoon placed over the diversion tunnel's intake tower, a structure that rose 230-feet from the lake floor and whose top lay 30-feet beneath the surface, the divers were tasked with dismantling one of its sides and removing twenty, 3.5 ton trash racks in order to reach the sluice gates at the tower's base.

Divers being dressed (L to R) Ron Titcombe; Bill Fitzgerald; Keith Gregson and 'Pony' Moore.

With the help of a floating crane to lift the heavy trash racks, the divers' worked their way progressively down the tower. While those at the shallower depths came away quite readily it was on the fifteenth trash rack, at a depth of approximately 200 feet, that divers' experienced their first set back.

Despite the maximum pull of the crane, the fifteenth trash rack was jammed into the tower frame and, like the next three, could only be removed by the use of plastic explosives inserted between the trash racks and detonated electronically from the surface.

Obstinate racks were not the only problem confronting the divers as they progressed towards the 200 feet depth. Physiological and psychological troubles also began to take their toll.

Combined with the freezing cold that numbed them to their bones, the divers were hampered in their work by zero visibility caused by decomposing vegetable matter suspended in the lake's water. Despite the use of a surface powered, 1,000 candle power underwater light, visibility was reduced, at best, to just a few inches. More often than not the divers worked in an inky blackness, a condition that led to more than a few interesting radio exchanges between the diver and those on the surface.

Chief Petty Officer W. T. Fitzgerald recalls being asked what he could see.

"Nothing!" Came his response. "Are your eyes open?" "I don't know! At 260 feet in the pitch black how do I know if my eyes are open if I can't see? I don't even know whether I'm conscious or not!" At the deeper depths the problems were compounded by nitrogen narcosis. A diver would go down, attach the crane to the next rack and return to the surface confident that he had completed his task. After an unsuccessful hoist another diver would descend to investigate. He, in turn, would report that the first diver had not attached the chains correctly, but that the problem was now rectified. A second failure would entail sending yet another diver down. He would return to report that both previous men had been under an illusion! Narcosis had caused them to have memory lapses in the middle of the job, leaving it only partially completed.

The final frustration would come when, after three divers had eventually prepared the rack for lifting, the crane cable broke and the team was back where it started.

Eventually, however, all of the trash racks were removed and the divers could concentrate on checking and repairing the leaking sealing device, twenty-eight, five-ton 'stop-logs'.

Because of the inhospitable conditions, the RAN imported from France several of the then new Cousteau constant volume dry suits to protect the divers from the freezing cold. Despite wearing increasing layers of undergarments and several sets of 'woolly bears' the intense cold still penetrated through, the divers finally settling on wearing heavy duty neoprene wet suits beneath the French dry-suits.

Designed to cope with pressure and temperature, the suits also permitted continual voice communications with the surface, a precaution that allowed the diver, while working at depth, to be quickly brought up to a higher level at the first sign of irrational comment brought on by narcosis.

Limited by decompression considerations, the diver's effective bottom time was reduced to a few minutes on each dive when working at the maximum depth.

After about 15 minutes at 260 feet it took nearly an hour-and-a-half of staged decompression to bring the diver back to the surface.

Trialing new methods of speeding up this ascent rate, the Navy gained valuable experience in greatly reducing the diver's underwater time by feeding him pure oxygen through his air hose during the shallower decompression stages. A procedure that, after 15 minutes on the Lake bed, reduced the diver's decompression obligation to thirty-six minutes! Decompressing divers working at the maximum depth was further assisted by the use of the Navy's submersible decompression chamber. Serving as an underwater 'elevator', the SDC offered the divers a rapid transit back to the surface enabling them to carry out their decompression in comparative comfort. However, because the only available crane was required for lifting trash racks and stop logs, the SDC had limited use.

The physiological strain of the deep diving meant that a man could only dive once in any twenty-four hour period, but for over eighty days the small team maintained its gruelling pace. On the surface between dives there was plenty to do; while one diver was down another was dressed and standing by for emergencies, others controlled the air hoses or monitored the radio and listened for signs of narcosis.

The onset of winter only added to the divers' problems. The water temperature dropped to freezing point, daily frosts froze the decking of the pontoon, and natural increases raised the water level of Lake Eucumbene by ten feet so that, towards the end of the job, the divers were working at depths close to 270 feet.

Excerpts from the dive log highlight the problems that the diving team faced on a daily basis.

14th March 1961 Depth 209 feet. On the ascent the diver's air hose fouled the shot line at 200 feet. He was unable to free himself and signalled for assistance. The standby diver descended and cleared the obstruction. The diver surfaced in good condition 78 minutes later.

14th March 1961 Depth 257 feet. The diver had apparently lost consciousness on reaching the depth. He failed to respond to signals and the order was given for the standby diver to enter the water and Fitzgerald to be hauled to the surface.

As the standby diver entered the water, Fitzgerald appeared at the surface still breathing but incapable of coordinated movement. The standby diver immediately pulled him down to the 90 feet decompression stop and escorted him up through the remaining stoppages. On reaching the surface 47 minutes later he was suffering from a severe headache and was partially overcome by the cold.

20th March 1961 Depth 213 feet On surfacing the diver was found to have a burst eardrum - the membrane had expanded outward and ruptured. The whole drum was bloody and flaked. The rupture was apparently caused by the ear-piece of the head phone preventing the outward pressure from equalising.

22nd March 1961 Depth 243 feet.

Diver surfaced and reported that the job had been completed. He was well and had conducted his dive satisfactorily. However, the next diver down reported that the previous diver had coupled up incorrectly. The first diver was convinced that he had done the job correctly.

With the problem of the leaking sluice gates isolated and eliminated, the divers' replaced the twenty trash racks and the task was finally complete.

>Breakout panel # 1 The Men from Snowy River The RAN diving team - specially selected to include the Navy's most experienced divers - consisted of Commander M. Batterham, OBE; Lieutenant Titcombe, MBE, Second-in-Charge; Medical Officer, Surgeon Lt. Cmdr. R. Gray; Chief Petty Officer W. T. Fitzgerald; Petty Officer Jake Linton; Leading Seamen Ingram; Moore; and Gregson; Able Seamen Jeffress; Creasey; Hills